Church

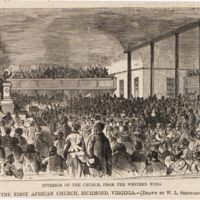

The end of slavery radically changed Virginia's churches, as many split into separate white and black congregations. Before the Civil War, most white and black Virginians sat in separate sections of the same churches. Virginia law had required that African American churches have white ministers, but in some congregations African American members became community leaders because of their roles in the church. After the Civil War, many African Americans established separate churches to achieve autonomy. African American churches served as schools and political gathering places, with some serving social welfare functions such as aiding people in economic distress and assisting in locating lost family members separated by slavery. Henry Williams, who became pastor of Petersburg's Gillfield Baptist Church, organized community service associations and assisted freedpeople in reuniting with family members who had been separated during slavery.

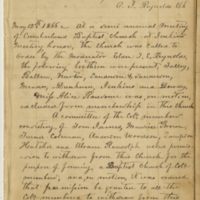

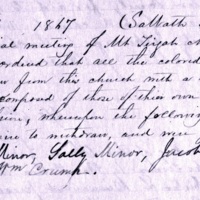

During the Civil War, representatives of several African American Baptist congregations in southeastern Virginia organized the Union Baptist Association. Others formed the Colored Shiloh Baptist Association in August 1865. One of its founders, Peter Randolph, voiced the desire of African Americans to turn away from "the kind of preachers we had had in the dark days of slavery," who had "denied our manhood and with their own hands had bought and sold human flesh." These organizations paralleled the many associations in Virginia for white churches (or for earlier churches with members of both races).

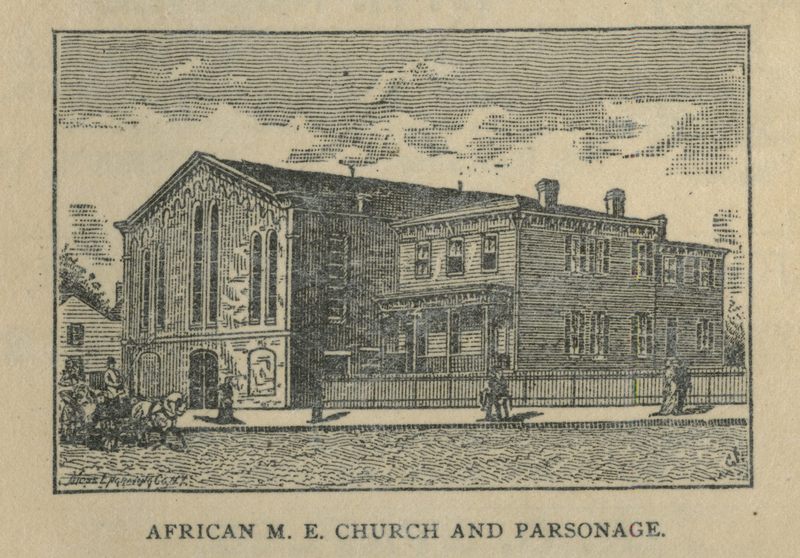

The majority of African American congregations in Virginia were Baptist, but freedpeople and their descendants also organized Presbyterian, Catholic, African American Episcopal, and African American Episcopal Zion congregations. The new churches erected by the state's African Americans during the final decades of the nineteenth century testify to the significance of church in their lives. In some towns and cities, African American churches were among the largest structures

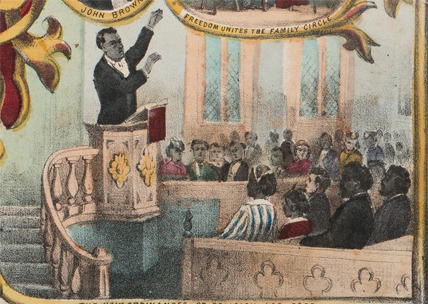

Because of the importance of religion to Virginia's freedpeople, their churches served as important gathering places for both community life and political organizations. Ministers often assumed influential leadership positions in local politics by virtue of their central roles in the community and because they were literate and often educated, which members of their congregations may not have been when first freed. The former slave Fields Cook (ca. 1817–1897) not only served as a Baptist minister in churches in the vicinity of Richmond, he also helped organized working men in the city, chaired a delegation of men who met with President Andrew Johnson in Washington in June 1865, and was a political leader in the state.

Like Henry Williams at Gillfield Baptist Church, many ministers and church members established beneficial, fraternal, and burial societies to serve their congregations and communities. By 1874, Richmond boasted dozens of organizations such as the Baptist Help of Richmond and the United Christian Sons. Some of these societies grew into substantial insurance companies and savings banks. During the 1880s, William Washington Browne (1849–1897), a formerly enslaved Methodist minister, transformed a temperance organization into a successful insurance company in Richmond, the Grand Fountain United Order of True Reformers.