Labor

Emancipation led to the creation of a new labor dynamic in Virginia. Former slaveowners no longer controlled the labor of their former slaves, and the formerly enslaved gained some but not complete control over their own labor. Many white people believed, in the words of a white Nelson County farmer, that "if you employ Freedmen there is great uncertainty of getting his labor." Some people therefore tried to force African Americans into stringent labor contracts that bound them in near servitude. One of the important tasks of the Freedmen's Bureau was to assist unskilled freedpeople in finding useful employment, as did many private organizations, such as the Freedmen's Union Industrial School in Richmond.

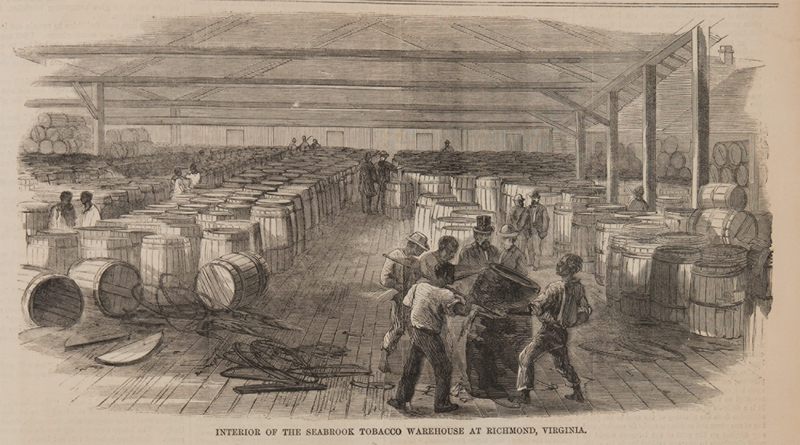

Thousands of newly freed African Americans left the farms and plantations where they had lived and labored and went to the cities, where paying work was hard to find. As a result, during the second half of 1865 the Freedmen's Bureau provided rations for thousands of people who had no resources to feed themselves. Governor Francis H. Pierpont reported that some former slaves feared that if they remained where they had lived while in slavery, they would be re-enslaved; and other freedpeople hoped, based on false reports, that they would receive forty acres of land and a mule. In January 1866 the General Assembly passed a vagrancy act that allowed local officials to arrest and hire out people who had no obvious employment. General Alfred H. Terry, the commanding officer in Virginia at the time, denounced the vagrancy act as "slavery in all but its name."

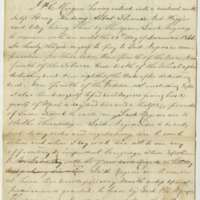

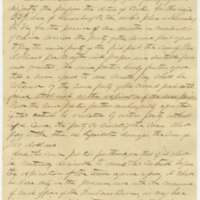

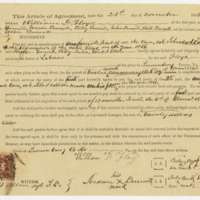

Local Freedmen's Bureau agents helped freedpeople negotiate and enforce labor contracts in the new free-labor economy, and sometimes intervened in court proceedings to protect their rights. Agents acted as judges to settle disputes over labor contracts. The agreements could also be enforced in local courts, and in some instances bureau agents appeared as witnesses to verify or testify about the terms of labor contracts. A contract between William D. Floyd and members of the Burnett family included a provision that allowed the parties to appeal to the Freedmen's Bureau to annul the labor contract. Many such contracts contained similar language, indicating that agents of the bureau often took part in negotiating labor agreements.

Labor agreements took many forms. Some were simple contracts that specified who would work for whom at what rate of pay. In June 1865, Hanover County farmer Slaughter B. Bullock contracted with five men and three women, including the children of one of them. He hired his former enslaved laborers to work for him for stated wages and a place to board at his farm. The agreement was unusual (and unusually fair) in that it allowed either party "to make any change they may choose at the expiration of each month."

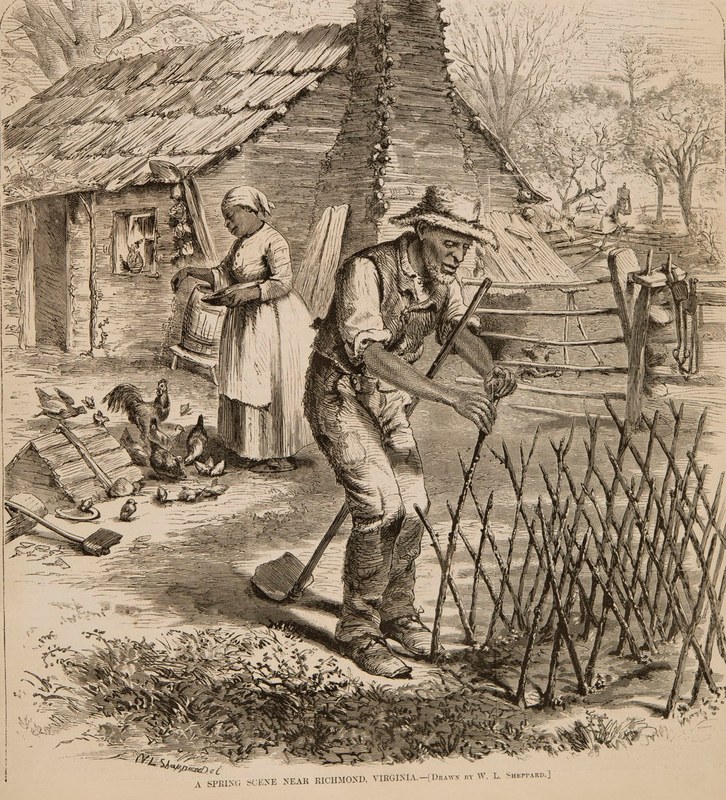

Others imposed obligations or restrictions on laborers. In Lunenburg County, William H. Eubank hired six African Americans to farm his land in 1866. In addition to specifying the pay, lodging, and rations the workers would receive, the labor contract required the workers to rise by dawn and be at work by sunrise. It allowed them one hour for dinner each day and required them to be polite and obedient and to labor at the direction of the landowner or his agent. The agreement also imposed restrictions on when the workers could leave the plantation or receive visitors. If any of the workers violated any provisions of the contract, he or she forfeited all benefits for the year.

Many contracts promised payment in the form of a portion of that year's crop. Called sharecropping, those agreements left farm laborers at the mercy of the weather and the harvest. If they failed to produce an adequate crop, they might have to borrow money and promise to pay it back from the earnings of the next season's crop, in effect binding them to remain where they were and continue to work under the same contract. In 1866 P. C. Morgan contracted with five men and women, whom he identified as belonging to his neighbors as he would have done during slavery. The workers would receive a portion of the corn, tobacco, wheat, and oat crops they raised, although seeds would be deducted from their portion. Deductions would also be made for any time lost to illness. Any breach of contract by the African Americans would result in forfeiture of all claims to payment and they could be forced to leave Morgan's Lunenburg County plantation.

Many freedpeople worked for themselves or earned money to purchase their own farms or small businesses. In Virginia's cities and towns, African American men and women owned or operated their own shops or businesses. For example, in April 1868, James B. Carter purchased a lot at the corner of Thirteenth and Hull Streets in the town of Manchester and opened a grocery store in partnership with Richard Smith. Carter had been a member of the state's constitutional convention that adjourned a few days before he purchased the lot, and he may have used some of the per diem allowance that he received for serving in the convention to pay for the property and open his business.

At the end of nineteenth the century, more African Americans owned their own farms in Virginia than in any other state. In Louisa County, for example, about 39 percent of African Americans owned farm land by 1900. The average black family's farm was smaller than the average white family's, but owners of land, even if relatively poor, were independent enough to escape some of the constraints faced by African Americans, whether formerly enslaved or formerly free, during the decades after the end of slavery.