Remaking Virginia

Even as the Civil War was still being fought, the status of almost half a million African Americans in Virginia began to change. They were no longer someone else's property—they were free. They anticipated the promise of change from their former status as slaves: the promises of education, political participation, and full citizenship. Yet, in their struggle to achieve these goals, freedmen and freedwomen faced the hostility of their former masters and the society that had long benefitted from their unpaid labor. United States troops and government officials reconstructing the Southern states were often indifferent to freedpeople's efforts to achieve full rights.

What challenges did African Americans face in their struggle to achieve what they believed freedom would bring them? What obstacles blocked African Americans' efforts to gain citizenship? How did white Virginians react to the end of slavery—the underpinnings of their economy and culture—and the changes that free African Americans expected in this new Southern world? How successful were African Americans after the Civil War in achieving their objectives? Did the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution significantly aid African Americans in their struggles? Remaking Virginia offers a look at the changing world that all Virginians faced during the post–Civil War years.

Emancipation radically altered labor, social, and political relations between the races. Black expectations of personal, political, and economic freedom after the war ran headlong into white resistance. Many whites, embittered by the war and desperately clinging to an antebellum model of race relations, used violence to enforce labor contracts, social mores, and claims to political supremacy. Republican leaders in Congress initiated a number of provisions to help protect the rights of freedpeople.

The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, established the formerly enslaved as citizens of the United States. The Fifteenth Amendment, passed in Congress in February 1869, granted the right to vote to African American men. Virginia was one of the former Confederate states required to ratify the Fifteenth Amendment to be readmitted to the United States. After ratification by three-fourths of the states, the amendment was certified as a part of the U.S. Constitution on March 30, 1870.

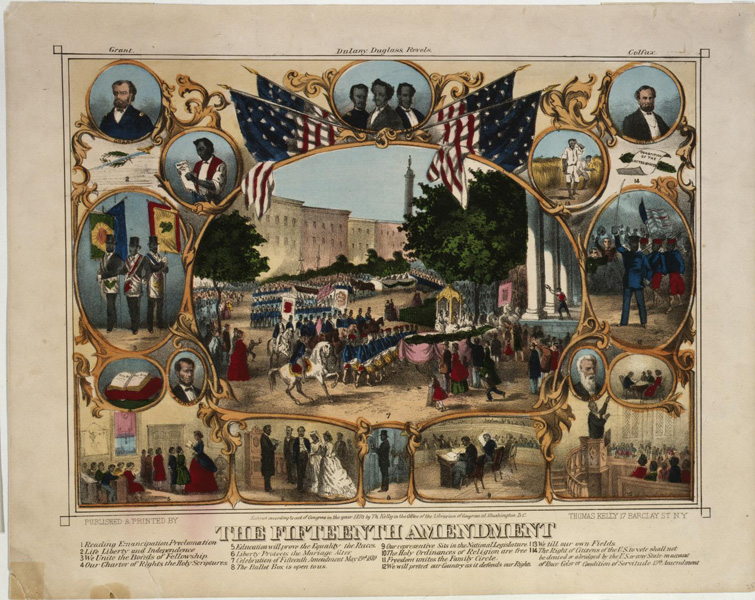

Please click on the image below to zoom in on different vignettes and read descriptions of their significance to the story of emancipation.

This lithograph contains seventeen separate images. At the top are three African American leaders, Martin Robison Delany, the first African American commissioned field officer in the U.S. Army and the "father of black nationalism;" Frederick Douglass, famed abolitionist and the best-known African American leader of his day; and Hiram Rhodes Revels, the first African American to serve in the U.S. Senate. At opposite corners at the top of the image are Ulysses S. Grant, then president of the United States, and Schuyler Colfax, then the vice president. Flanking the central image at the bottom are Abraham Lincoln, enshrined by many as the "Great Emancipator," and the radical abolitionist John Brown, depicted as a hero for his famous raid on Harpers Ferry in October 1859.

The other vignettes depict aspects of African American life after slavery—education, farming, and fraternal organizations, as well as religious, family, and military life. These images reflect the hopes and desires of African Americans for self-determination and advancement through full inclusion in American society, and their ability to pursue, unimpeded, their own American dreams. The central image shows a massive parade that took place on May 19, 1870, in Baltimore, Maryland, celebrating the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment