Voting and Citizenship

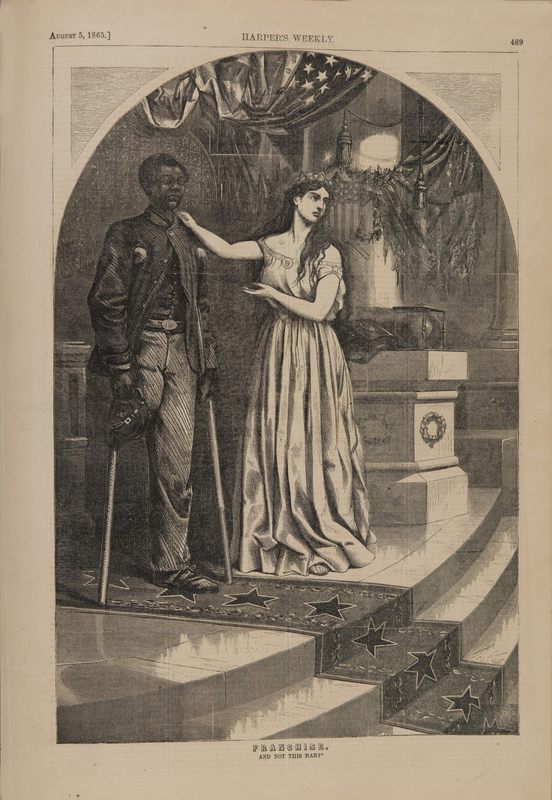

When the Civil War ended and slavery was abolished, many African Americans, especially veterans of the United States armed forces, believed that freedom should be much more than an absence of slavery. They believed it should include full rights and responsibilities of citizenship, including the right to personal liberty, to own property, and to take part in public life by voting and holding office.

In the spring of 1865, African American men in Norfolk organized the Colored Monitor Union Club to demand full rights of citizenship. On May 25, 1865, more than a thousand of them attempted to vote, and that summer they published Equal Suffrage. Address from the Colored Citizens of Norfolk, Va., to the People of the United States to document and explain their need for the vote: "We do not come before the people of the United States," they began their address, "asking an impossibility; we simply ask that a Christian and enlightened people shall, at once, concede to us the full enjoyment of those privileges of full citizenship, which, not only, are our undoubted right, but are indispensable to that elevation and prosperity of our people, which must be the desire of every patriot."

In other communities, such as Hampton, Richmond, and Williamsburg, men organized political clubs for the same purpose. African Americans held a state convention in Alexandria on August 2–5, 1865. One of their declarations insisted that "the laws of the Commonwealth shall give to all men equal protection; that each and every man may appeal to the law for his equal rights without regard to the color of his skin; and we believe this can only be done by extending to us the elective franchise, which we believe to be our inalienable right as freemen, and which the Declaration of Independence guarantees to all free citizens of this Government and which is the privilege of the nation. We claim the right of suffrage."

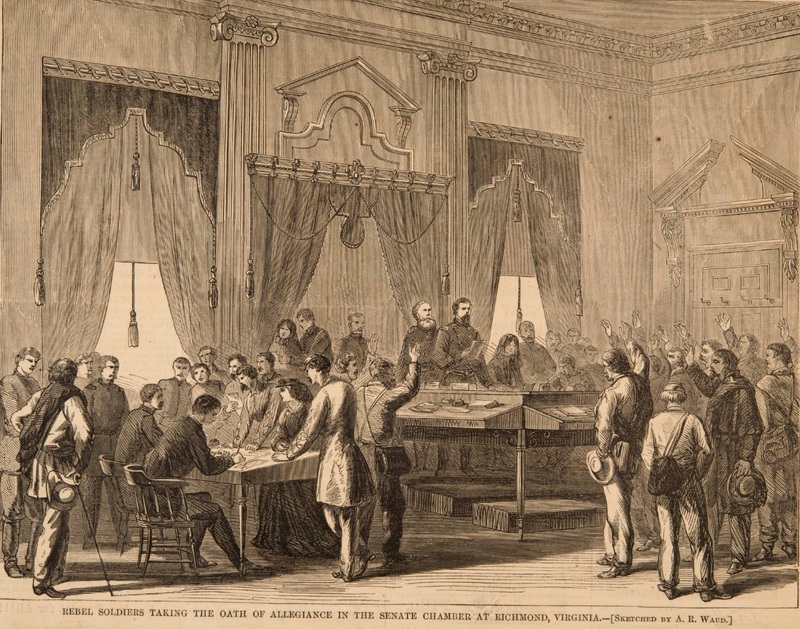

At the same time that African Americans argued for the right to vote, many white Virginians could not vote because they had supported the Confederacy. In June 1865, the General Assembly restored voting rights to some of those white men, but the federal government required men who had supported the Confederacy to take an oath of allegiance to the United States or obtain a presidential pardon before they could regain the suffrage.

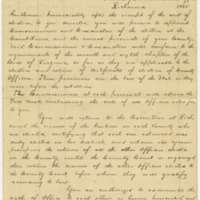

As elections for local officials, members of the assembly, and Congress approached in the summer of 1865, the Unionist Republican secretary of the commonwealth, Charles H. Lewis, issued instructions for registering voters. By an act of General Assembly, he advised registrars, "[T]he right to vote and hold office is restored to all officers attached to militia regiments, disbanded before the 1st day of July 1862, who have not, since the 1st day of January 1864 voluntarily given aid and comfort to the enemies of this State and to the United States." Attorney General Thomas R. Bowden, also a Unionist Republican, published two official opinions in response to questions about who could vote and who was eligible to hold office.

No African American men voted in the 1865 election. The members of the General Assembly elected at that time served until 1867. In 1865, the voters also elected members of the House of Representatives, but Congress did not seat any senators or representatives from Virginia until Congressional Reconstruction in the state ended in January 1870.