Citizenship and Public Life

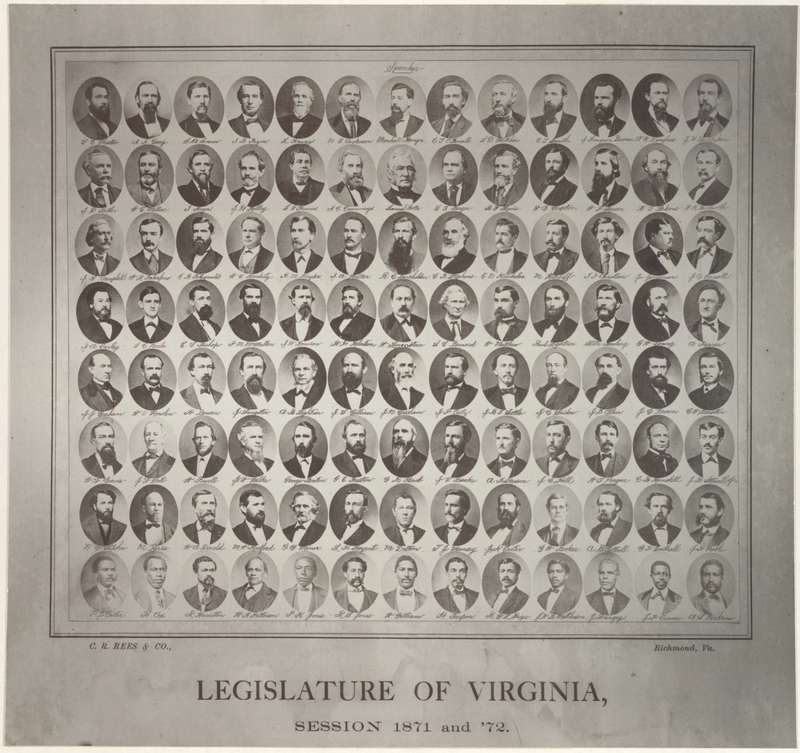

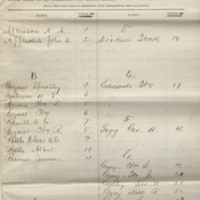

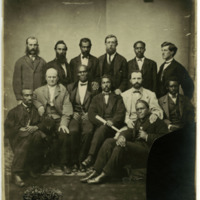

The Virginia Constitution ratified in 1869 guaranteed African Americans the right to vote and hold public office. The Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, ratified in 1870, prohibited the United States government and the government of any state from denying the vote to any citizen "on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude." Between the October 1867 election of members of the Constitutional Convention and the end of the General Assembly session of 1889–1891, nearly a hundred African American men won election to the convention, the House of Delegates, and the Senate of Virginia.

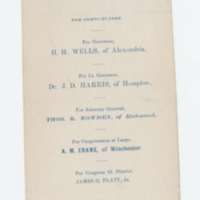

On the same day that voters ratified the new constitution, they elected members of the General Assembly and statewide officers. For governor, Radical Republicans nominated Henry Horatio Wells, then serving as governor by appointment of the commanding general of the First Military District. The nominee for attorney general was the incumbent Thomas R. Bowden, a Unionist Republican who had been elected attorney general of the Restored Government in 1863. For lieutenant governor, the radicals nominated an African American, Joseph Dennis Harris, a physician who had been born into slavery in North Carolina, grew up in Ohio, and spent time in the Caribbean before settling in Virginia, where he practiced medicine and became involved in Republican Party politics.

Moderate Republicans nominated a rival ticket with New York native Gilbert Carlton Walker for governor, and Virginia Unionists John Francis Lewis for lieutenant governor and James Craig Taylor for attorney general. The Conservative Party endorsed the moderate Republican ticket in order to present a united opposition to the Radical Republicans. The moderate Republicans won the statewide offices and Conservatives won large majorities in both houses of the General Assembly.

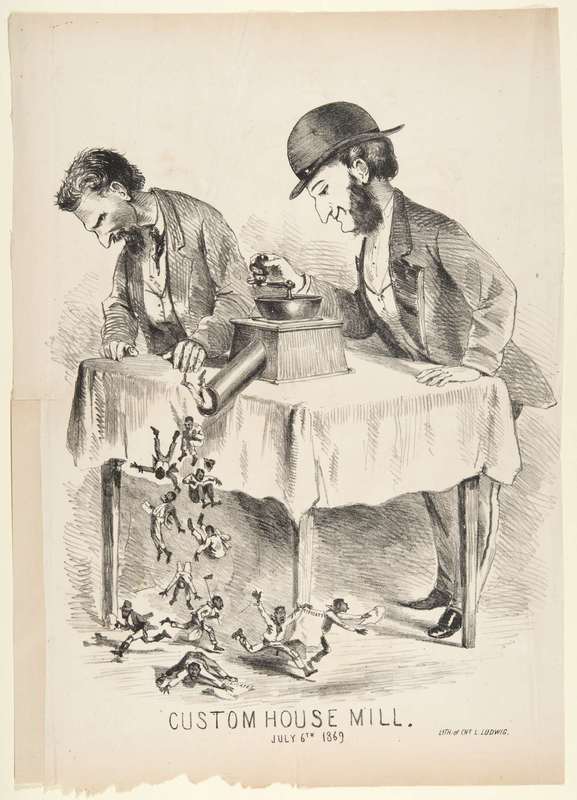

White Virginians feared that unscrupulous politicians would use government jobs in the post office or federal customs houses to create powerful Radical Republican political machines with the support of African American voters. Black Virginians served in county and city governments as well as in the General Assembly and as appointees to patronage jobs with the federal government, although how many African Americans won election to local offices or held federal positions is unknown.

African Americans in Virginia never enjoyed all the rights of full citizenship they were entitled to as a result of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. One right that Virginia courts seldom granted them was the right to serve on juries. Even after the Civil Rights Act of 1875 prohibited states from excluding African Americans from juries, few or none served in state or local courts in Virginia. The Supreme Court's decisions in three cases in 1880, two of which arose in Virginia, declared that Congress was justified under the Fourteenth Amendment in making that prohibition, but Virginia judges often found ways to avoid calling or seating black men on juries.

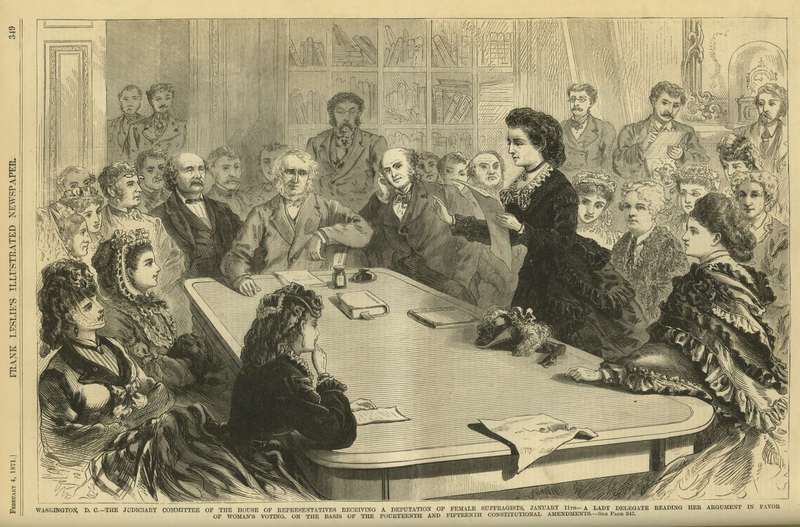

The years following the abolition of slavery produced many calls for change in the state's political and cultural practices. Some white Virginians embraced the changes that took place, but others opposed them. In the reforming atmosphere of the 1860s, a small number of white Virginians advocated granting the vote to women. In 1870, Anna Whitehead Bodeker, of Richmond, founded the Virginia State Woman Suffrage Association, the first organization in the state to advocate votes for women. It included several notable Radical Republican reformers. On November 7, 1871, Bodeker tried to vote but was refused.

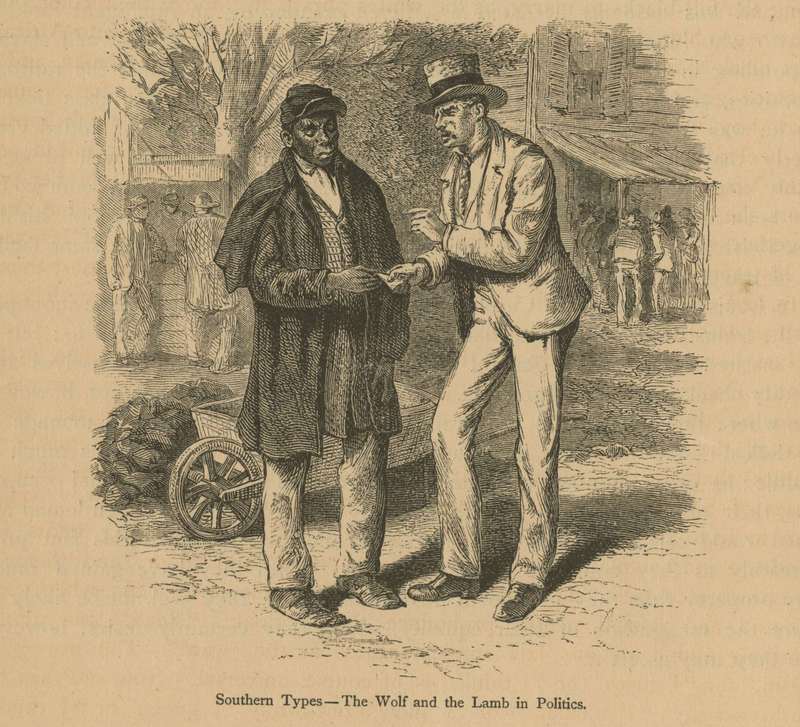

African Americans exercised powerful political influence in Virginia during the brief existence of the Readjuster Party at the end of the 1870s and early in the 1880s. In 1879, black Virginians, most of whom were Republicans, made an alliance with politicians who organized the Readjuster Party to refinance (readjust) the public debt left over from before the war. The Readjusters’ leaders, most notably Senator and former Confederate general William Mahone, welcomed black voters and officeholders into the Readjuster Party. Together, black and white Readjusters and Republicans won majorities in both Houses of the General Assembly in 1879 and in 1881, and they elected all the statewide officers in the latter year. The biracial coalition revived fears of Radical Republican domination of the state. By the end of the nineteenth century, white supremacists who dominated the Democratic Party of Virginia had made it so difficult for African Americans to vote and win election to public office that no black man won election to the General Assembly after 1889 and few won election to local offices after the end of the 1890s.