Military Service

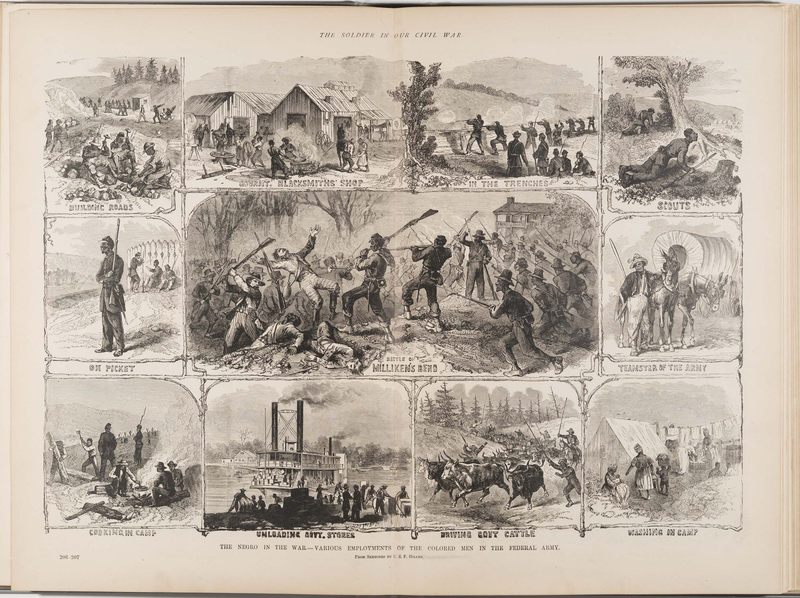

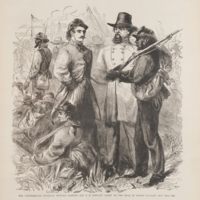

African Americans performed services for both the Union and Confederate armies during the Civil War. In the earliest days, they performed manual labor, such as digging entrenchments and driving wagon teams. In the spring of 1861, for example, Virginia's engineer department hired enslaved laborers to help construct the defensive works at Gloucester Point, for which their owners were paid fifty cents per day.

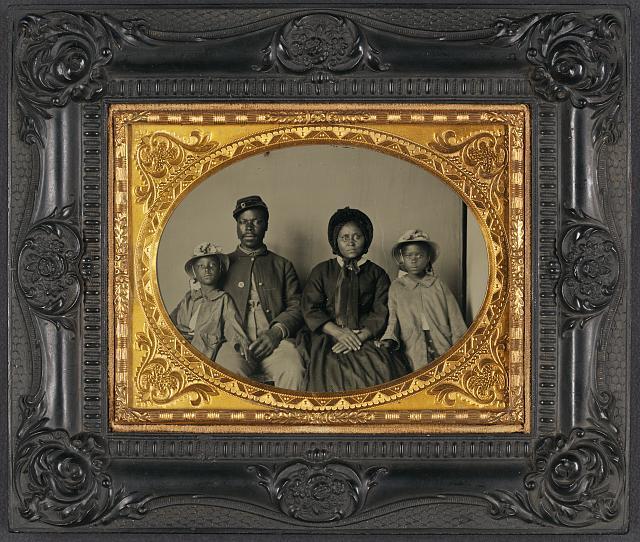

In 1863 the U.S. Army allowed African Americans to enlist as soldiers, a move that created heated debate about whether African Americans were able to be effective in the field. About 200,000 African Americans served in the U.S. Colored Troops and more than 5,000 African Americans enlisted into U.S.C.T. regiments that mustered in Virginia. Many saw their fiercest fighting on Virginia soil at places like New Market Heights, Fort Gilmer, Saltville, and the Battle of the Crater near Petersburg. More than fifteen African Americans from Virginia earned the Medal of Honor, six of them for outstanding service in their native state—Powhatan Beaty, William Harvey Carney, James Gardiner, Miles James, Edward Ratcliff, and Charles Veal.

Like many members of the U.S.C.T., William Harvey Carney (1840–1908), had been born enslaved. His father escaped from Norfolk to Massachusetts and secured Carney's freedom. In 1863, Carney joined the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, which led the charge on July 18, 1863, against Fort Wagner, in South Carolina. When the flag bearer was shot, Carney saved the American flag and planted it on the parapet. When the regiment fell back, he retrieved the flag, despite receiving several serious wounds. Honorably discharged in June 1864, Carney received the Medal of Honor for his heroism on May 23, 1900.

African American soldiers served in numerous combat roles. They conducted raids and assaults, guarded railroads and lines of communication, garrisoned forts, and served as spies. John C. Underwood, a federal judge in Virginia, testified in 1866 about a conversation he had with a white Richmond man who described the enlistment of African American troops as the "heaviest blow" to the South, because "their weight thrown into the scale decided the contest against" the Confederacy. On April 3, 1865, units of the U.S.C.T. liberated Richmond and helped put out the fire that destroyed much of the city's business district.

For several months after the end of the war, the army stationed soldiers, including African Americans, throughout Virginia to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation and protect the freedpeople. Many white Virginians expressed outrage at the presence of African American soldiers in the role of occupiers. White Lunenburg County residents petitioned Governor Pierpont to remove the African American troops who had been quartered at the county seat, because their presence was "repugnant and humiliating to our feelings," and they feared the troops would have an "improper and injurious influence on our former Slaves."

African Americans proved that they were the equals of white soldiers and sailors in their service during the Civil War, but the debate on African American military service went further. In proving themselves capable of fulfilling military and civic duty, African American soldiers opened the door to the larger debate on full citizenship, including the right to vote. Some army veterans, such as Peter Jacob Carter, had long and successful careers in public life after the war. Carter (1845–1886) had been born into slavery in Northampton County and served in the 10th Regiment U.S.C.T. After attending Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, he won election to the House of Delegates in 1871, served for eight consecutive years, and became a leader in the Republican Party.